A Tussle with Autonomy and Ownership: Land Ownership among Indian Women

BY Aysha Abdulla/ August 30, 2025

DESIGNED BY Riddhi Jain

Owning land in rural India is a sign of social and political prestige. Although for rural women, owning land is a distant dream of social and domestic security with a promise of autonomy.

and Ownership in India is governed differently on the basis of religion, state, and the type of land in various scenarios and although the inheritance laws are spelt out on the legislative front, the implementation and effectiveness of them remain uncertain. In the recent decades, scholars and academics have taken up research on the land ownership patterns in India on the basis of three surveys mainly. Across the globe, landownership can be crucial for women in terms of autonomy, decision making and improvement in socio-economic conditions. The lack of comprehensive country-wide estimates indicating the gender gap in land ownership across countries signals towards greater systemic disinterest on the issue. Increased land ownership among women is not the end goal in and of itself but is the means to achieving greater equality.

L

Increased land ownership among women is not the end goal in and of itself but is the means to achieving greater equality.

The NFHS-4 (National Family Heath Survey), IHDS-II (India Human Development Survey) and ICRISAT (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics) longitudinal panel data has been criticised and utilised across research papers and scholarly articles to examine agricultural land ownership across country. NFHS is conducted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and mainly collects data for the purpose of recording population dynamics, health indicators, emerging issues in the domain of health and family welfare so as to support policy makers and programme implementing agencies in setting a benchmark in data. On the other hand, IHDS aims at documenting the changes in the lives of Indian families in a time of rapid transformation in the country and ICRISAT is known for conducting agricultural research across various countries.

Pictured: Illustration by James Steinberg via Pinterest

NFHS-4, which was conducted in the year 2015-16, especially does not separate agricultural land from all land owned and neither does it probe further into other aspects of being a land owner, which would reveal the nature of the ownership. Simultaneously, the NFHS-4 data lacks consistent regional patterns otherwise observed in both IHDS-II and ICRISAT datasets where the southern states are leading and eastern states are falling behind in terms of women’s ownership of agricultural land. There is a reversal in the regional pattern in NFHS-2 dataset, wherein the eastern states are thriving in terms of women’s ownership of agricultural land instead of the southern states (Agarwal et al., 2021). This makes the dataset prone to criticism, as historically, the southern states have witnessed a more matrilineal culture and were also some of the first states to amend the Hindu Succession Act 1965 (HSA) in favour of women.

The amount of land held by people, compared on the basis of gender, was not taken into account in the IHDS-II which resulted in a failure to measure the magnitude of the inequality in this aspect. The survey instructed the respondents to list the top three owners of agricultural land in their household, however, the question circumvents the cases where women own land, but not enough to be included as the largest landowners in the family. This implies that the data does not acknowledge a gender dimension. Lastly, the dataset does not include questions about land owned individually, versus land owned by a household, comparing this across various parameters, including gender. All of this points to important questions that the IHDS-II has not focused on leading to an incomplete understanding of the land-owning dynamics in rural India, especially in context to the role women have in land ownership.

From 2010 up until 2014, ICRISAT data covered largely the same set of households each year from 30 villages initially across 8 states, namely Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka in the south, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh in the west and Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha in the east (Agarwal et al., 2021). 95 per cent of the ICRISAT dataset though consists of hindu households subjecting the research to the Hindu Succession Act majortively (Agarwal et al., 2020). While the ICRISAT dataset provides consistent data over the years, it is also a limitation in comparison to IHDS and NFHS since the sample consists of a limited number of households.

Taken together, these surveys tend to underestimate or misrepresent women’s landownership by ignoring the scale of holdings, conflating household and individual ownership, or relying on narrow samples. Such gaps are not just methodological; they weaken the policy response. Without accurate and nuanced data on how much land women own, under what terms, and with what degree of control, interventions like joint titling, credit access, or inheritance reforms risk being tokenistic rather than transformative.

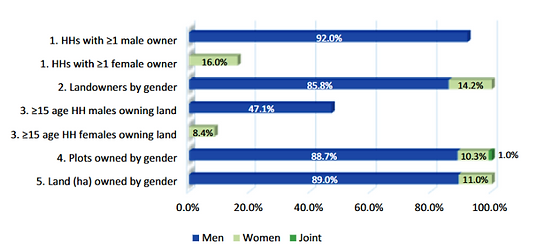

Source : Agarwal B. (2021). Comparing indicators of gender inequality in land ownership [graph]. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(11), 1807–1829.

In 2023, Niti Aayog and the United Nations in India, signed the Government of India-United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2023-2027, under which the Sustainable Development Goal 5 emphasises achieving gender equality and equal rights for all girls and women. Despite this, most countries lack comprehensive country-wide estimates of the gender gap in land ownership. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has made efforts to collect gender-specific land ownership data but only 20 countries have reports on who owns the land on the basis of gender. Most countries have data on who mainly operates the holding (Agarwal et al., 2020). Shipra Deo, Landesa’s Director, highlighted in an interview with IndiaSpend how improving the methodology and gender sensitivity of NFHS and other land ownership datasets can be further aligned with the UNSDG standards (Choudhury et al., 2021).

Inter-Gender and Intra-Gender Gap in Land Ownership

In India, especially in patriarchal societies, it is far more acceptable for a widow to receive a share of her husband's property after his death than for a daughter to receive a share of her father’s property after his death. Laws are said to be amended to benefit daughters in situations of inheritance but legislations do not necessarily translate into implementation at the various levels that the government functions at (Agarwal et al., 2020). However, the inheritance received by either daughters or widows is not nearly sufficient to bridge the inter-gender land ownership gap.

Valera et al.’s Women’s Land Title Ownership and Empowerment: Evidence From India spanned across four states, namely Bihar, Eastern Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Odisha and covered 8,640 households. According to the study, of the 11,920 plots, about 89 per cent were acquired through inheritance, showing the prominence of acquisition through inheritance in east India. A similar report published by Landesa and UN Women in 2013 about Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh specifically, showed that about 73 per cent of all land types are acquired through inheritance, 25 per cent is purchased and approximately 2 per cent is received through government programmes or leasing (Nagarajan, 2014). About 14 per cent of the women involved in the study own up to 11 per cent of the agricultural land in rural households. After the amendment of the Hindu Succession Act (1956) in 2005, women's land acquisition through inheritance increased from 5.5 per cent in 1956-2005 to 6.4 per cent in 2006-2015. The amendment made to the HSA allowed daughters to become coparcenary owners by birth. In the meanwhile, about 87 per cent of men have acquired land through inheritance after the 2005 reform, highlighting the fact that inheritance rights have remained biased against women (Valera et al., 2018).

Also ,according to the ICRISAT survey, 87.5 per cent of the plots across all the states involved were owned individually by men and only about 10.2 per cent of the plot by individual women. It is also important to note that when it comes to land ownership and inheritance laws, age is considered before other factors that are involved. Landowners, both male and female, are on an average 51 to 52 years old with the years of schooling being much lower among owners in comparison to non-owner family members. The inter-gender educational gap among land owners is also significant since the male owners have generally

2

Pictured: Illustration by Hannah Parkar via Pinterest

completed more years of schooling in comparison to women. The dataset does not draw any clear connection between the years of schooling and the older land owning population. Although amongst the younger population attainment of higher education leads to further disinterest in farming and portrays interest in pursuing other avenues.

Another dimension of the differences between male and female landowners is their marital status. Of the land available, 46 per cent of female land owners are widowed in comparison to widowed, male owners which form a mere 6 per cent. Moreover, only 41 per cent of all women who are landowners are household heads and they usually tend to be mothers or wives of the actual household heads (Agarwal et al., 2020).Therefore owning land does not necessarily give them authority in the household which is in sharp contrast to the 89 per cent of all male owners who are household heads.Although it must be acknowledged that most women receive land ownership at a stage in their life when they cannot fully utilise it to their benefit. And while they may be the land owner, they might not be in the position to command the utilisation of the land. It has been observed in the Landesa - UN survey that approximately 61% of the women in the survey do not interact with Revenue Office officials and there is a general lack of confidence and habit in terms of communication with the officers. This lack of communication with revenue officers manifests itself into a lack of control and authority over one's own land. Regular communication with officials can help in opening doors to solving other larger governance issues and helps women in attaining information that can be acquired only by interacting with these officials (Kelkar et al., 2013).

The Religious Conundrum of Land Ownership in India

Land ownership in India is prominently governed by the Hindu Succession Amendment Act (2005), Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act (1937) and the Indian Succession Act (1925). Despite there being amendments in the Hindu Succession Act (HSA) some states are still grappling with gender-biased inheritance laws. For example, the Supreme Court in November 2024, heeded a PIL filed and sought responses from Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand governments regarding inheritance laws. The petitioner argued that under UP Revenue Code 2006, when a female acquires land via her father, upon her demise the land must transfer to the husband's heirs rather than her own. The provision also disentitles a woman’s ownership right over land inherited through her father in case of marriage.

Under Hindu Personal Law regarding land ownership, women can own and manage their own land independently, due to the 2005 amendment, it also includes the ownership of agricultural land. This is significant since under HSA 1956 women could only inherit property directly acquired by the fathers while the ancestral property was reserved for the sons. (Khan, 2025). However, after the amendment of Hindu Succession Act only 2.3 per cent of plots are jointly owned. Furthermore, no plots are jointly owned in the eastern and central states. This represents the lack of recognition and implementation of the amendment as, if coparcenary rights had been recognised, it would be expected that the number of jointly owned plots would increase (Agarwal et al., 2020).

Pictured: Illustration by Francesco Bongiorni via Pinterest

Under Muslim Personal Law all the land is available for inheritance only after the death of the original owner. A female heir receives one third of the share of estate property while men get two thirds of it, the justification given for the same is that men are responsible for the financial provisions (Khan, 2025). The Muslim Personal Law fails to recognise that women can also be responsible for financial provisions in a household, in such a situation the inheritance received by the female heirs may be insufficient.

Christian and Parsi inheritance is governed by the Indian Succession Act (ISA) 1925, wherein christian widows receive one third of the estate property and the male and female descendants get two thirds of the estate property equally divided (Sircar & Oxfam India, 2016). Parsi’s are governed by the same law with addition of the specific amendments introduced in 1939 that apply only to the Parsi population of the country (Khan, 2025).

Religious leaders often play a critical role in influencing societal views on various topics and land ownership is one of them. In religious communities, in this case the the Hindu and Muslim communities, religious leaders propagate the idea that women cannot and should not own land and these beliefs are adopted by many followers, including women, who are made to believe that they do not have the right to inherit any land from their parents because of their gender. On the other hand, about 20 per cent of Hindu women and 5 per cent of Muslim women indicated that their religious leaders do not believe in their right to inherit land from their husbands, not denying their faith and trust in those leaders (Kelkar et al., 2013).

Bina Agarwal, a professor of Development Economics and Environment at the University of Manchester, UK, has extensively written about land, livelihood and poverty rights. She has been researching the rural economy since the mid 1970s and has made significant contributions towards the research into women’s land ownership. Bina Agarwal’s studies bring forth the disadvantaged position of women farmers when they lack command and managerial authority over productive assets. A lack of control over their own assets has made it difficult for women farmers to avail credit facilities, inputs and technology (Bose, 2016).

Religion is integral to the socio-cultural fabric that impacts land ownership rights in India and lack of awareness paired with the influence of religious leaders further creates a gap between women and their rights.

Women’s Land: Welfare, Autonomy and Sustainability

Land ownership acts as a deterrent against gender based domestic violence and as a source of security. A 2006 study in Uttar Pradesh showed that only 6 per cent of women owned land, less than 1 per cent participated in government training programmes, only 2 per cent had access to institutional credit and, only 8 per cent of those women had control over their agricultural income (Sircar & Oxfam India, 2016). Absence of women in these spaces can be indicative of their lack of knowledge about these programmes, and the lack of information required to make decisions and exercise their autonomy thereof.

Pictured: Illustration by unkown via pinterest

Furthermore, the lack of formal documentation regarding land ownership is appalling in India. Of the total plots reported in the Landesa-UN Women study, only 60 per cent are formally documented with a title deed or a patta. A quarter of the plots lack any type of documentation and the remaining have various white paper documents, which lacks the revenue authority seal. According to the same study in 78 per cent of the case the women had no land document to their name. In India, administrative inefficiency and societal taboos have exacerbated the problems of firstly, women holding land and secondly, accurate classification and recording of said land.

Equal land ownership rights for women further help in achieving UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 5 and according to FAO if women had equal access to productive resources as men, farm yields could increase by 20-30 per cent, this would lead to a 4 per cent increase in total agricultural output in developing countries, potentially reducing global hunger by 12-17 per cent (Khan, 2025).

Women are significantly more likely to have decision making authority when they are the de facto head of the household. Women that owned land and their names were on the title deed are much more likely to take part in making decisions regarding plot use (Kelkar et al., 2013). Simultaneously, agriculture has been progressively feminised in India. Approximately 70 per cent of the agricultural labour in India is performed by women cultivators and agricultural labourers. Lacking recognition of women as farmers systematically shuns them out from institutional credit, government training and causes lack of control over agricultural income.

Lacking recognition of women as farmers systematically shuns them out from institutional credit, government training and causes lack of control over agricultural income.

The gender gap among men and women must be bridged so as to not create a society wherein certain sections of society are severely disadvantaged and the allocation of resources favours the already privileged counterparts. Women owning land and having control over it creates a reliable safety net that protects them from social and economic discrimination. Organised efforts towards collecting landownership data paves way for furthering gender equality, disseminating rights and easing the process of acquiring and transferring land.

Keywords

Land ownership, Women’s land rights, Gender inequality, Inheritance laws, Hindu Succession Act 2005, Muslim Personal Law 1937, Indian Succession Act 1925, Inter- and intra-gender gap, NFHS-4, IHDS-II, ICRISAT dataset, Household vs. individual ownership, Agricultural labour feminisation, Property documentation (Patta), UN SDG 5

References

Agarwal, B., Anthwal, P., & Mahesh, M. (2021). How many and which women own land in India? Inter-gender and intra-gender gaps. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(11), 1807–1829. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2021.1887478

Agarwal, B., Anthwal, P., & Malvika, M. (2020). Which women own land in India? Between divergent data sets, measures and laws. In Global Development Institute, GDI Working Paper (No. 2020–043). The University of Manchester. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/GDI/gdi-working-paper-202043-agarwal-anthwal-mahesh.pdf

Bose, S. (2016, January 17). “Owning property empowers women in unique ways”: An Interview with Bina Agarwal. The Caravan. https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/bina-agarwal

Centre for Social Justice. (2023, May 9). Women’s land rights in India: What’s missing from our land laws? India Development Review. https://idronline.org/article/gender/womens-land-rights-in-india-whats-missing-from-our-land-laws/

Choudhury, P. R., Choudhury, P. R., & Indiaspend. (2021, March 10). Why we don’t know how much land women own. Indiaspend. https://www.indiaspend.com/land-rights/why-we-dont-know-how-much-land-women-own-734247

ICPSR. (n.d.). India Human Development Survey (IHDS) series. ICPSR (Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research). https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/series/507

Kelkar, G., Landesa, & UN Women. (2013). THE FOG OF ENTITLEMENT: WOMEN AND LAND IN INDIA. In ANNUAL WORLD BANK CONFERENCE ON LAND AND POVERTY. https://www.landesa.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Fog-of-Entitlement-Women-and-Land-in-India-261-Kelkar.pdf

Khan, A. (2025, April 14). Workers or owners? The case of women farmers in India. https://sprf.in/workers-or-owners-the-case-of-women-farmers-in-india/

Nagarajan, R. (2014, March 6). Barely one in ten women own land, brothers most anti sisters inheriting land: Survey. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/barely-one-in-ten-women-own-land-brothers-most-anti-sisters-inheriting-land-survey/articleshow/31403305.cms

Press Information Bureau. (2022, August 22). Role of National Family Health Survey (NFHS). https://www.pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1847431

Sircar, A. & Oxfam India. (2016). Women’s Right to Agricultural Land: Removing legal barriers for achieving gender equality. In Oxfam India Policy Brief: Vol. No. 19 [Policy brief]. https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/618600/bn-womens-right-agricultural-land-india-070716-en.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

UN Women. (2013). Report on The Formal and Informal Barriers in the Implementation of the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act 2005 in the context of Women Agricultural Producers of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. https://www.landesa.org/wp-content/uploads/hsaa-study-report.pdf

Valera, H. G. A., Yamano, T., Puskur, R., Veettil, P. C., Gupta, I., Ricarte, P., & Mohan, R. R. (2018). Women’s Land Title Ownership and Empowerment: Evidence From India. In ADB Economics Woeking Paper Series: Vol. NO. 559 [Journal-article]. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/453696/ewp-559-women-land-title-ownership-empowerment.pdf

The views published in this journal are those of the individual author/s and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the team behind Beyond Margins, or the Department of Economics of Sophia College for Women (Autonomous), or Sophia College for Women (Autonomous) in general. The list of sources may not be exhaustive. If you’d like to have the complete list, email us at beyondmarginssophia@gmail.com

_edited.jpg)