Cooperative Societies in India: The Legacies of AMUL and Indian Coffee House

BY Annapoorna Mariam Fatima/ August 11, 2025

DESIGNED BY Anuya Shindolkar

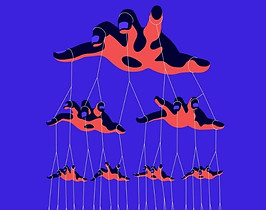

Emerging from the shadows of industrial capitalism, worker cooperatives have long offered a grassroots path to economic justice—rooted in solidarity, mutual aid, and the historical struggles of working people.

rofit controls the world and dominates our economic ecosystem, serving as the central organising principle of capitalist production. Within this framework, profitability is not merely a goal but an imperative, often pursued at the expense of social welfare, equity, and human dignity. Rooted in the Industrial Revolution, capitalism is characterised by private ownership of the means of production, extraction of surplus value, capital accumulation, and profit maximisation (Wright, 2014). A defining feature of this mode is its dependence on wage-labour, often resulting in exploitative forms of economic subjugation and alienation–seperating workers from the products of their labour, their own human potential, and their fellow workers.

Furthermore, production under capitalism is entirely dependent on market forces of supply and demand, governed by imperatives of profit maximisation. This mechanism does not permit socially efficient allocation of resources. Instead, resources are distributed based on purchasing power and profitability, often excluding essential but non-lucrative needs. For instance, many areas of rural America did not have electricity in the 1930s because private investors deemed that the relative lack of profits did not justify the costs of supplying electricity to these regions (Wright, 2014). Capital’s interests lie in reducing the cost of production as much as possible, whilst simultaneously increasing the profit, and preventing the worker from exercising control over the process of production.

"P

A defining feature of this mode is its dependence on wage-labour, often resulting in exploitative forms of economic subjugation and alienation–seperating workers from the products of their labour, their own human potential, and their fellow workers.

This simple structural antagonism underlies the history of the labour struggles, from revolutions and union movements to state-led suppressions and social mobilisations. At the same time, the vicissitudes of the capitalist economy leave many people unemployed at any given time, unable to find work because of undervalued skills, insufficient investment, outsourcing to countries where labour is cheaper, and so on. Unsurprisingly, a system driven by the exploitation of labor and rooted in the antagonistic relationship between worker and owner fails to produce socially harmonious outcomes (Bellucci & Weiss, 2020). Only in the ideal world of standard neoclassical economics, which assumes perfect knowledge, perfect capital and labor flexibility, the absence of firms with “market power,” the absence of government, and in general the myth of homo economicus—the purely “economic rational” man—does societal harmony exist (Wright, 2014).

Pictured: Illustration by Unknown via Pinterest

Relying exclusively on the capitalist mode of production exacerbates social and economic inequalities. In response, a range of social movements have arisen in opposition to the social evils of capitalism, and cooperativism is one such movement, specifically worker cooperativism. Potentially the most “oppositional” form of resistance, as it organises production in fundamentally anti-capitalist ways: through workers’ democratic control over production and, in some cases, collective ownership of the means of production. In the worker co-op, labour has power over capital, or “labour hires capital.” Unlike the conventional business models wherein by contrast, capital maintains control, i.e., “capital hires labour”, worker co-op exists, not primarily for the sake of maximising profit but for satisfying some social needs. They “represent within the old form [i.e., the capitalist economy] the first sprouts of the new” (Marx, 1894).

Structurally, worker cooperatives are owned and democratically governed by the workers themselves, each of whom typically holds one share and one vote, regardless of position or seniority. This model contrasts with producer cooperatives, where ownership lies with producers (as in the case of Amul), and with traditional businesses, where control is concentrated among shareholders and executives. In worker cooperatives, profits are distributed among worker-owners based on their contribution, often measured by hours worked, rather than by capital investment, as is common in shareholder-driven models. This shift in distribution logic reflects a deeper realignment of economic power: privileging labor over capital and embedding equity into the firm’s governance and financial structure.

Worker cooperatives are grounded in the principles of economic democracy and social equity. Their primary mission is to provide stable, dignified employment rather than to maximise profits for external investors. They emphasize solidarity over competition, human-centered values over pure efficiency, and long-term sustainability over short-term gains. Because decision-making power resides with those directly impacted by business operations, suchcooperatives tend to be more accountable, resilient, and community-oriented than traditional corporate firms.

In India, where economic disparities, rural distress and unemployment remain pressing issues – cooperative enterprises offer a compelling alternative model. Two notable examples that illustrate the potential and challenges of this approach are Amul, a producer-owned dairy federation based in Gujarat, and the Indian Coffee House, a nationwide chain of worker-managed cafes spread across the country. Though structurally distinct, both demonstrate how cooperative principles can be adapted to local conditions, scaled to national relevance, and rooted in democratic control.

Amul

Since its founding in 1946 and the subsequent White Revolution in 1970, Amul has evolved into one of the world’s largest milk producers, transforming India from a milk-deficient country into the global leader in dairy production. Today, with a daily milk procurement of over 27 million litres and a retail footprint spanning more than 5 million outlets, Amul is not merely a brand but an institution woven into the everyday life of Indian households. The Anand Milk Union Limited, commonly known as Amul is an Indian dairy brand owned by the cooperative society, Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), based in Anand, Gujarat, and governed by 3.6 million milk producers (AMUL).

Amul was founded as a response to the exploitation of small dairy farmers by private traders and intermediaries who exercised near monopolistic control over milk pricing and distribution in the Kaira district of Gujarat. At the time, milk prices were arbitrarily set, giving Polson Dairy an effective monopoly in milk collection from Kaira for supply to Mumbai, backed by state-sanctioned monopolies and government support. This arrangement denied farmers access to alternative markets, leaving them vulnerable to price manipulation.

Pictured: Illustration by Unknown via Pinterest

Polson’s monopoly meant farmers were denied access to alternate buyers or markets. Meanwhile, India was spending large amounts of scarce foreign exchange to import dairy products from New Zealand and Europe, despite having a substantial domestic dairy base. Frustrated with the exploitative trade practices (which they perceived as unfair), the farmers of Kaira, led by Tribhuvandas Patel, approached Vallabhbhai Patel, who advised them to form a cooperative. This would allow them to bypass middlemen and directly supply milk to the Bombay Milk Scheme.

In response, Sardar Patel delegated Morarji Desai to organise the farmers. Following a key meeting in Chaklasi, the farmers resolved not to sell milk to Polson and instead formed a cooperative. Because most producers were marginal farmers contributing only 1–2 litres of milk daily, milk collection was decentralised, village-level cooperatives were established. By June 1948, the Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers’ Union Limited (KDCMPUL) began pasteurising milk for the Bombay Milk Scheme. With the help of Verghese Kurien, this initiative scaled rapidly and led to the formation of India’s first modern dairy cooperative. In 1970, the movement culminated in the launch of India’s White Revolution, which transformed dairy production across the country and marked a turning point in national food security (Heredia, 1997).

Amul’s model has had a profound impact on rural India, particularly through economic empowerment of small-scale and marginal farmers. By ensuring regular and fair payments, the cooperative has enhanced income stability and has strengthened local economies. Notably, a significant portion of Amul’s producers are women, contributing meaningfully to gender empowerment and enhancing the role of women in rural livelihoods. Beyond the local scale, Amul has been instrumental in transforming India into the world’s largest milk producer, achieving self-sufficiency in dairy production and shaping the trajectory of the country’s agricultural development.

2

Despite its tremendous success, Amul does not qualify as aworker cooperative in the strictest sense; rather, it is a producer cooperative in which the primary stakeholders are milk producers, not plant workers. However, its participatory governance structure and deeply democratic ethos make it a compelling and influential example of cooperative enterprise. While Amul’s model prioritizes producer empowerment over worker ownership, its scale, inclusivity, and institutional longevity make it one of the most compelling cooperative success stories in India.

Indian Coffee House

The Indian Coffee House (ICH) is a direct and enduring example of the worker cooperative model. It emerged in the late 1950s when the Coffee Board of India decided to close its chain of government-run coffee houses. Faced with the threat of mass unemployment, displaced employees responded by forming cooperative societies to take over the ownership and management of the outlets themselves. The first Indian coffee house under the cooperative model opened on 8 March, 1958, in Thrissur (Pillai, 2007).

Today, with around 500 outlets across the country, ICH maintains a strong nationwide presence. It has long served as a cultural and intellectual hub, particularly for India’s socialist and communist movements, and has played a notable role in shaping the political and public discourse of multiple generations.

Pictured: Illustration by Satish Gangaiah via Pinterest

Although coffee cultivation in India can be traced back to the 16th century, the concept of coffee house began to gain popularity in the 18th-century, particularly in Madras and Calcutta. However, under British rule, these establishments were racially segregated; access was restricted to Europeans, with Indians prohibited from entry. In response to these exclusionary practices, the idea of an "Indian Coffee House" began to take shape in the late 1890s.The first such outlet, named India Coffee House, was launched by the Coffee Cess Committee under the Indian Coffee Board in 1936 at Churchgate, Bombay. By the 1940s there were nearly 50 Coffee Houses all over British India. Following the 1947 partition, Pakistan inherited several branches, whichcontinued to serve as important cultural venues fostering intellectual and political discussions. At its peak in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the chain operated 72 outlets across the subcontinent. However, due to declining business and shifts in policy, the Coffee Board began shutting down its establishments by the mid-1950s.

Around this time, A.K. Gopalan—a prominent Indian communist politician, and one of the 16 members of the Communist Party of India members elected to the first Lok Sabha—urged workers from the coffee houses to form a cooperative and take over business from the Board (Pillai, 2007). Responding to the threat of widespread job loss, the workers of the Coffee Board began a movement and compelled the Coffee Board to agree to hand over the outlets to the workers who then formed Indian Coffee Workers' Co-operatives and renamed the network as Indian Coffee House.

The Indian Coffee House operates through a network of federated worker cooperatives, with each regional branch managed by its own society, such as the Indian Coffee Workers’ Cooperative Society in Thrissur or the Delhi Coffee Workers’ Cooperative Society. These cooperatives function with strong democratic control, where all major decisions, including those related to pricing, hiring, and expansion–are made collectively by worker-members through elected committees. Each worker holds an equal share in the cooperative, ensuring both equitable ownership and a fair distribution of profits among all members.

The Indian Coffee House model has had a substantial impact by preserving employment for thousands of workers who were at risk of redundancy, offering them job security through collective ownership. Over the decades, these cafes have evolved into important cultural institutions, serving as intellectual hubs for artists, writers, and political thinkers, particularly during the 1960s and ’70s.

Pictured: Illustration by Joey Guidone via pinterest

Despite intense competition from modern private cafes and multinational chains, numerous Indian Coffee House branches have managed to endure. Their continued relevance is often attributed to a combination of nostalgic appeal, affordable pricing, and a deeply loyal customer base.

However, the Indian Coffee House model faces notable challenges. Financial strain remains a concern in several regions, where declining patronage and the inability to match the marketing and investment power of private players have placed some cooperatives under considerable stress (Mohan, 2006).

The aforementioned enterprises were revolutionary in their own way, emerging during the formative years of a newly independent India and continuing to shape its socio-economic landscape today. Amul and Indian Coffee House represent two different strands of cooperative enterprise in India: Amul demonstates how cooperatives can scale, modernise, and integrate with national development strategies, while Indian Coffee House exemplifies the pure spirit of worker ownership and democratic self-management.

The aforementioned enterprises were revolutionary in their own way, emerging during the formative years of a newly independent India and continuing to shape its socio-economic landscape today.

Fundamentally, worker co-operatives are guided by a set of shared principles, including voluntary and open membership, democratic member control, economic participation by members, autonomy and independence, and concern for community. Historically, such cooperatives have served two central roles: providing a vehicle for economic stability and, later, for political expression, often emerging during times of economic distress, and connected to larger social justice and political movements. Often arising in times of economic or social distress, worker cooperatives have acted as reactive but empowered strategies pushing back against values and systems that negatively impacted communities and individuals (Wright, 2014).

Historically, such cooperatives have served two central roles: providing a vehicle for economic stability and, later, for political expression, often emerging during times of economic distress, and connected to larger social justice and political movements.

In an era marked by rising inequality, gig work precarity, and deepening environmental crises, worker cooperatives offer a humane, inclusive, and sustainable model of business. While not without limitations, their core principles—equity, participation, and solidarity—align with the values required to build a just and resilient economy. The Indian cooperative movement, as exemplified by Amul and the Indian Coffee House, demonstrates that alternatives to conventional capitalism are not just possible, they are already embedded in our history.

Keywords

Worker cooperatives, Producer cooperatives, Democratic ownership, Amul, Indian Coffee House, Labor movements, Collective resistance, Economic alternatives, Ownership structures, Grassroots innovation, Non-capitalist production, Institutional alternatives, Labor-centric systems

References

Bellucci, S & Weiss, H. “The Internationalisation of the Labour Question.” Macmillan.

Curl, J. (2009). “For All The People”. PM Press.

https://pmpress.org/index.php?l=product_detail&p=432

Harris, N & Jervis, R. (2024). “Worker Cooperatives for a Democratic Economy”. Berghain Journals.

https://doi.org/10.3167/dt.2024.110102

Marx, K. (1894). Das Kapital Vol. III Part V.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/

Pillai, N. (2006). Coffee Housinte Katha.

Wright, C. (2014). “Worker Cooperatives and Revolution”. BookLocker.

worker cooperatives and revolution: history ...ResearchGatehttps://www.researchgate.net › ... › Marxism

“Worker Cooperatives- A Powerful Force for Justice and Democracy.”(2008) Grassroots Economic Organizing. https://geo.coop/articles/worker-cooperatives-powerful-force-justice-and-democracy

The views published in this journal are those of the individual author/s and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the team behind Beyond Margins, or the Department of Economics of Sophia College for Women (Autonomous), or Sophia College for Women (Autonomous) in general. The list of sources may not be exhaustive. If you’d like to have the complete list, email us at beyondmarginssophia@gmail.com