From Opportunity to Obstacle: Mumbai’s Mirage?

BY Nethra Venkatraman/ August 09, 2025

DESIGNED BY Loyana Chakraborty

Beyond the Skyline - A closer look at how Mumbai’s rapid vertical expansion is leaving behind its workforce who form the crux of this city. Those who sustain this city now find themselves being locked out of it.

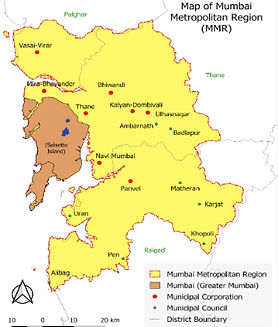

umbai’’ formerly known as ‘Bombay’ is often referred to as the City of Dreams, a title earned not merely from its film industry or glamour, but from the millions who have come to the city with nothing, and built something meaningful. While the official population of Greater Mumbai stands at 1.82 million per the 2011 Census, the broader Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), which includes Thane, Navi Mumbai, and other suburbs, is home to over 20 million people, making it one of the most densely populated urban agglomerations in the world (Census, 2011). With a per capita income of INR 2.74 lakh in 2022-23 (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Intervention), the city serves as India’s financial hub, housing major institutions like the Bombay Stock Exchange, Reserve bank of India and prominent banks such as State Bank of India, HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, Axis Bank. These are complemented by media giants, multinational companies and a thriving informal sector. Together they form the backbone of a city that contributes around 7% to India’s GDP, provides large-scale industrial employment and accounts for approximately one-third of all income tax collections in the country, cementing Mumbai’s stature as the financial capital of the city (IOSR-JBM, 2018). For decades, Mumbai has been a symbol of upward mobility, from textile workers to traders to tech professionals, filmmakers. However, in recent times, this has changed. While the city still attracts ambition, sustaining a life here has become a different challenge altogether.

"M

DeMap (n.d.). [Mumbai City map of India][Photograph]. RedBubble.

"Mumbai City Map of India - Bohemian" Canvas Print for Sale by deMAP | Redbubble

In the past few years, the cost of real estate in the city has skyrocketed, driven by insufficient land, infrastructural upgrades and speculative investment, to name a few causes. There was a time when premium and ultra luxury neighbourhoods were limited to areas like South Mumbai and Bandra, but now they have expanded to cover a large area of the city, especially the suburbs. This poses an important question: Are Mumbai’s property prices truly justified, or are they pushing out the very people who power this city? Is the city still a gateway to opportunity, or has the cost of pursuing that dream become too high?

Are Mumbai’s property prices truly justified, or are they pushing out the very people who power this city? Is the city still a gateway to opportunity, or has the cost of pursuing that dream become too high?

Over the past 5 years, Mumbai’s real estate market has experienced a significant surge. The average prices of a house in Mumbai increased by 6% in 2024, and are predicted to increase by 6.5% in 2025 (Reuters, 2025). When we measure the increased price of Rent per Square Foot in Mumbai, across zip codes, we see a minimum average rise of 2% and a maximum rise of 65% across the city. For a household earning INR 5–6 lakh per annum, this means spending nearly 50% of their income on rent, leaving little room for savings or emergencies.

Rent per square foot is a common method for calculating the cost of renting a property, particularly in commercial real estate. It represents the monthly or annual rent amount divided by the total square footage of the space.

1

1

To illustrate the growing inaccessibility of housing, the supply of affordable and mid-income housing units (priced up to INR 1 crore) in Mumbai dropped by 31% in just one year, falling from 8,763 units in 2023 to 6,062 units in 2024 (Business Standard, 2025). While this is a reflection of a single data point, it points to a deeper and more alarming trend, one where basic housing options are rapidly slipping out of reach for most. As brought to light in Knight Frank India’s Affordability Index Report (2025), most developers are not taking up projects focusing on low-income buyers, even though the major demands of housing come from them. In newly connected areas like Versova and Kandivali, developers and investors are launching luxury and ultra-luxury projects, or even just purchasing land in the anticipation of a future increase in interest rates and land prices. This creates a distorted market where speculative investors, who buy homes for profit rather than to live in, and the affluent are favoured over the city’s large working population.

This creates a distorted market where speculative investors, who buy homes for profit rather than to live in, and the affluent are favoured over the city’s large working population.

Infrastructure mega-projects like the Mumbai Metro, Coastal Road and Eastern Express Freeway, have further accelerated this trend. While these developments aim to improve connectivity and simplify travel for the population, areas connected to these have witnessed a surge in the property rates. The Coastal Road, specifically, is being built to connect South Mumbai to the Western Suburbs, running along the western coast of the city. It is to be a 36 km, 8-lane expressway that will improve connectivity in Mumbai, and shorten commute times by a large extent. This infrastructural project alone contributes to a 5-15% rise in real estate prices across the western suburbs (The Economic Times, 2024). As a result, areas that were on the outskirts of the city, once considered affordable are now slipping out of the reach of the workforce. Due to the Coastal Road project alone, there has been a greater number of redevelopment projects being taken up, especially in South and Central Mumbai, where older buildings are being replaced by newer luxury projects. (Times Now, 2024) This trend not only reduces affordable housing but also deepens social segregation, concentrating wealthier residents while displacing lower-income communities. While these developments are boosting market value, they are also reinforcing barriers to access. The resulting economic divide is reflected in a reduced availability of affordable housing and greater opportunity in select areas leaving many with fewer housing choices. Both ownership and rental markets have become less accessible to the middle- and lower-income groups, exacerbating existing inequalities.

While the paper will not address the social dimension of housing, it is important to acknowledge that this economic stratification is deeply entrenched in social realities. This argument is illustrated by a study conducted on the Lallubhai compound (a resettlement site in Mankhurd, Mumbai) that brought to light the intense marginalisation faced by lower-caste women, which is marked by inadequate infrastructure and fractured social ties, experiencing heightened vulnerability. Discriminatory practices in Mumbai’s rental market, further marginalised sections, adding a social dimension to the housing crisis (Ayyar, 2013).

_JPG.jpg)

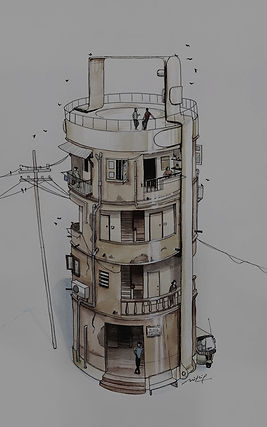

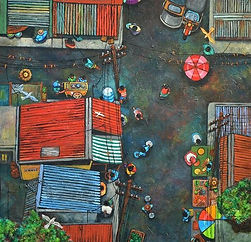

Pictured: Illustration by Unknown via Pinterest

The real problem isn’t just that property prices are increasing, it’s that they’re rising much faster than working class incomes.

2

The real problem isn’t just that property prices are increasing, it’s that they’re rising much faster than working class incomes. In Mumbai, while real estate keeps getting more expensive, wages have remained stagnant. Real wage growth across India has been at 0.01%, with many states witnessing a decline (India Ratings and Research, 2024), and in Mumbai, especially, salaries for middle-income workers have barely inched up by 0.4% (Business Standard, 2025). Evidently, wage growth has shown little to no improvement over the last five years, highlighting how wide the gap has now become between housing costs and salaries. This gap is what makes the city feel less and less affordable for the average person. A white-collar worker in Mumbai earns between INR 3 lakh to INR 5 lakh per annum, depending on the area, while mid-level professionals (with 5-10 years of experience) earn between INR 8 lakh to INR 15 lakh per annum, across roles such as marketing executives, software developers, teachers, architects, financial analysts, etc. (Economic Times, 2025). Simultaneously, a modest 1-BHK apartment in a relatively suburban area like Goregaon or Andheri costs upwards of INR 1.2 crores. Goregaon has witnessed an exponential 115% increase in property prices, and Andheri has nearly doubled over the last decade, with current costs averaging around INR 30,000 to 40,000 per square feet. This illustrates the stark contrast between what people earn and what they need to survive. The drop in the number of homes priced under INR 1 crore hits the working class the hardest. Since their income hasn’t kept up with housing costs, a lot of people are being pushed to live way out in the suburbs or settle for rentals, placing greater financial strain and compromising their quality of life due to longer commutes, reduced savings, and less access to amenities.

BHK is a common real estate abbreviation of a house having a Bedroom-Hall-Kitchen. The number added before this abbreviation is the number of bedrooms the house will have.

The National Housing Bank’s Residex data reveals that Mumbai is one of the least affordable cities in India, with national affordability ratios (house price to income) standing at 11, which implies that a person would need 11 years of full income to purchase a house in India. In Mumbai specifically, this ratio is at an all-time high of 14.3 (Business Today, 2025).

2

Tiwale, S. (2021) [Map showing the Mumbai Metropolitan Region along with the municipal corporations and councils] [Photograph]. ResearchGate. Map showing the Mumbai Metropolitan Region along with the municipal corporations and councils.

Due to the rising cost of housing in the city, many residents have opted to relocate to suburbs like Vasai, Virar, and Kalyan. While these areas offer more affordable housing, the trade-offs are significant. Commute times from these suburbs to workplaces can exceed 90 minutes, and residents face infrastructural gaps, especially access to multispecialty hospitals, and higher education institutions, as noted by the Vasai-Virar City Municipal Corporation (VVCMC). Adding to this stress is Mumbai’s chronic congestion, a result of its narrow, linear geography, growing number of private vehicles, underdeveloped road infrastructure, and ongoing metro construction that further reduces road space. A traveller in Mumbai spends a minimum of 2 hours in traffic (Economic Times, 2019), with the city recording 18.5 km/hr as the average speed, the slowest in India. Commuting from these suburbs often involves a combination of local trains, buses, and auto-rickshaws, which translates to spending hours on the road. For many, long-distance travel has become a normal part of daily life. A study by Bansode et al. (2020) notes that such commuting routines result in not only wasted time but also decreased productivity for working individuals.

Mumbai’s housing affordability crisis is displacing essential workers, including teachers, healthcare professionals, and public service employees who can no longer afford living in the city. This ongoing trend risks creating a shortage of vital services in the urban core, which could undermine the city’s overall functionality and resilience, while also widening the socio-economic divide.

For those not looking to buy houses, the renter’s market is not doing well either. Monthly rents for a modest 1-BHK in these areas lie between the range of INR 30,000 to INR 50,000 depending on the amenities, location and building. The rent is similar in Goregaon as well. These figures highlight how ‘mid-range’ suburbs in Mumbai also place a significant burden on the population. This structural strain is substantiated by a study conducted in 2023 which discussed consumer perceptions on rental burden and the search for sustainable living solutions. It brought to light that over 40% of the middle and lower-income households in Mumbai spend over 30% of their income on rent, highlighting how this rental burden correlates with a reduced quality of life, including overcrowding, longer commutes, and limited access to essential amenities, furthering urban inequality (Mujawar, 2023).

It brought to light that over 40% of the middle and lower-income households in Mumbai spend over 30% of their income on rent.

3

Furthermore, speculative investments by high-net-worth individuals and Non-Residential Indians (NRIs) warp the market. Many luxury apartments lie vacant, held as investment assets rather than homes (The Indian Express, 2025). In areas like Worli, over INR 4,800 crore worth of ultra-luxury deals were recorded in just 2 years, yet a significant portion of these units remained unoccupied. Similarly, in Lower Parel property prices are an average of INR 43,000 per square foot. Despite having a limited end-user demand, it has seen a dramatic surge in high-end construction projects. According to a 2024 report by Knight Frank India, Mumbai saw a 27% year-on-year jump in unsold housing inventory, especially in the premium segment. This spike played a major role in the overall 3% increase in unsold units during that time. The fact that there’s an oversupply of high-end homes but a shortage of affordable ones highlights deeper issues in the city’s real estate priorities and planning. What compounds this imbalance is the absence of a vacancy tax or an empty house penalty, which can discourage hoarding, used extensively in cities like Paris and Vancouver. In Mumbai, currently, there is no disincentive for leaving homes empty, allowing speculative capital to dominate the market, all while genuine home-seekers are unable to acquire a house.

Non-Residential Indian

3

Many luxury apartments lie vacant, held as investment assets rather than homes.

It’s also important to examine how urban planning regulations have contributed to exacerbating these inefficiencies. Particularly, Mumbai’s outdated zoning laws and poorly enforced Floor Space Index (FSI) policies. FSI, which determines the maximum permissible built-up area on a plot by calculating the ratio between total floor area and land size, plays a critical role in shaping urban density, infrastructure planning, and property valuation. Yet in Mumbai, weak enforcement and arbitrary revisions of FSI limits have enabled overbuilt luxury projects in select pockets, while affordable housing remains constrained by restrictive thresholds elsewhere. Historically, Mumbai restricted the FSI to 1.33, limiting the amount of floor area developers could construct relative to the plot size. Recent amendments have increased FSI to 3 for residential plots and 5 for commercial plots, but these higher allowances apply only along major thoroughfares. Since nearly half of Mumbai’s roads are only about 9.2 to 13.4 meters wide, most buildings in these areas are granted lower FSI allowances. This results in significant underutilisation of land across the city. Additionally, while developers lobby for higher FSI allowances and expedited Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) clearances, their commitment to building affordable housing and completing those quotas remains inconsistent. Industries have pushed the government to increase their incentives, like Transferable Development Rights (TDR), a mechanism that allows landowners to transfer their developmental rights from one area to another area where development is permitted, and relaxed clearance norms, because supply needs to be boosted, yet, the projects that are prioritized are the mid to high-end societies, where the profit-margins are better.

Local regulations that dictate how land can be used within specific areas.

As it stands for the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) model, have fared little better. Critics say the scheme tilts toward developer profits, not residents’ well-being. It was reported that over 500 SRA projects have failed to commence since 2005, affecting more than one lakh slum dwellers (The Times of India, 2020). Many projects are stalled due to ongoing land disputes that question ownership. This issue becomes complicated when the areas occupied by the slums are reserved for amenities or fall under the Coastal Regulation Zones (CRZ) which need to strictly follow a set of regulations given by the government to protect and manage coastal areas, balancing development with environmental conservation. However, those who are re-housed often end up in cramped, poorly lit flats with scant ventilation, trading one set of sub-standard conditions for another. The ongoing Dharavi Redevelopment Project, although far from unproblematic, offers a contrasting model, attempting to integrate housing with transit, healthcare and livelihoods. With an approximate budget of INR 90,000 crores, the plan includes several modes of transport around the area, schools, hospitals, and commercial zones, aiming to re-house over a million people. While the concerns about eligibility and displacement remain, the aim of the project highlights what an inclusive approach to slum upgradation can look like.

4

4

Pictured: Unkown Illustration via pinterest

5

The Maharashtra government has also launched several initiatives aimed at addressing affordability and inclusivity. The most prominent is the MHADA housing scheme, which offers subsidised houses, through a lottery system for the economically weaker sections, low-income groups and middle-income groups, across Mumbai. In 2025, the state revealed its new policy, Majhe Ghar, Majha Adhikar (My house, My right), with an investment of around INR 70,000 to construct over 35 lakh houses by 2030, prioritizing slum rehabilitation, rental housing and housing for women, senior citizens, and industrial workers. This policy also recommends a government land bank to streamline affordable housing development and through an updated IT system, establishing greater transparency. These schemes do mark a step forward and show that Mumbai is trying to do better, however their success will depend entirely on steps taken further and implementation methods.

In contrast, cities like Vienna and Singapore have taken a more proactive approach to housing by implementing strong public housing initiatives. These efforts have helped stabilise real estate prices and keep housing affordable. For example, Vienna’s social housing model includes over 200,000 public housing units, making up around 60% of the city’s total housing stock. Rent prices are based on tenants' income, with typical rents for an 80 square meters flat ranging from 500 to 600 euros, and as low as 250 euros for long-term residents. A key takeaway is their commitment to building mixed-income, municipally owned housing across the city and not just the urban centres. Singapore's public housing policy, primarily managed by the Housing and Development Board (HDB), focuses on providing affordable housing to its citizens. They are able to provide quality houses to Singapore’s population largely because the government owns and manages most of the land. This centralised control allows for co-ordinated urban planning, bulk construction as well as price regulation, which ensures that housing remains affordable across income groups. These cities have established that there are ways in which development can take place while also valuing the people who make that development sustainable. While Mumbai still lacks the scale of public land ownership or regulatory centralisation found in these cities, the core principle of housing affordability achieved through sustained state intervention, can be adopted while planning infrastructure around the city.

Houses or flats provided by the government at low rents for people who have low incomes.

Property prices keep climbing, yet the actual value being offered to middle-class newcomers is hard to gauge. While new infrastructure and ongoing urbanisation have contributed to rising property values, the rate of these increases appears disproportionately high compared to the tangible benefits received by the average middle-income resident. This trend challenges the assumption that escalating prices signify genuine progress., It highlights the need to reassess current urban development priorities. Mumbai’s real estate trajectory over the past decade reveals a growing disconnect between soaring property prices and the city’s socio-economic landscape. The combination of rising housing costs and stagnant wage growth has made homeownership increasingly unattainable for the middle class. This gap between cost and value is further widened by the nature of supply being created in the market. Private developers are incentivised to build ultra-luxury and luxury property, focusing on high margins, and affordable housing remains constantly under-supplied due to low incentive and limited regulatory enforcement. Despite schemes and policies that aid people, the lack of incentives and mandatory quotas for affordable housing implies that the market will continue to cater to speculative capital rather than actual housing needs.

If this pattern continues unchecked, Mumbai risks evolving into a city accessible only to the wealthy, questioning its long-standing title of ‘City of Dreams’. Once a place where migrants, workers, entrepreneurs alike could build a life, it now moves towards a place defined by exclusion. Reclaiming Mumbai, calls for strong, co-ordinated action across sectors. This includes implementing stronger rental regulations such as the Model Tenancy Act, 2021 to protect tenants from arbitrary hikes and broker exploitations. This act introduces written tenancy agreements, caps security deposits, and establishes Rent Authorities to resolve disputes swiftly. It also requires forcing the mixed - income housing mandates in all new developments that benefit from public incentives or FSI relaxations. At structural levels, reforms such as the public land bank, proposed in the Maharashtra Housing Policy, 2025, offer a chance to re-plan land use centred around equity and inclusion. Currently, the way Mumbai is headed, without such systemic shifts in the way land and housing is managed, the housing market will simply deepen inequality further and weaken the city’s social fabric, eroding the very spirit that made the Mumbai city a home for all.

5

Keywords

Mumbai Housing Crisis , Wages Up, Affordable Homes, Rent Burden, Workers Pushed Out ,Luxury Vacancy, Urban Divide, No Vacancy Tax, Real Estate Crisis ,Affordable Housing, Mumbai Metro, City Of Dreams, Vienna Model

References

Ayyar, V. (2013). Caste and gender in a Mumbai resettlement site. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/caste-and-gender-in-a-mumbai-resettlement-site

Ashar, S. (2013, September 4). 17 years on, govt realises SRA has failed Mumbai. Mumbai Mirror. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/17-years-on-govt-realises-SRA-has-failed-Mumbai/articleshow/22271732.html

Bansode, B. M., Mandal, S., Parmar, A., Patel, D., & Pal, P. (2020). Research on issues of traffic in Mumbai and finding its solutions. International Journal for Innovative Research in Technology, 6(9), 1–5. Research on Issues of Traffic in Mumbai and Finding Its Solutions

Buisness Standard. (2025, January 28). Supply of homes priced up to Rs 1 crore falls 30% in 2024: PropEquity. Business Standard. Supply of homes priced up to Rs 1 crore falls 30% in 2024: PropEquity | News - Business Standard.

Business Standard. (2025, June 24). Gautam Adani highlights Dharavi redevelopment project, slum healthcare at AGM 2025. 'Our most transformative project': Gautam Adani on Dharavi redevelopment | Company News - Business Standard

CNBC-TV18. (2025, June 20). Why Dharavi residents are wary of the redevelopment project. Why Dharavi residents are wary of the redevelopment project - CNBC TV18

CNBC-TV18. (2025, June 20). Mumbai housing affordability improves: Knight Frank report. Mumbai's housing affordability improves, NCR worsens: Knight Frank India Report - CNBC TV18

Economic Times. (2019, September 3). Indians spend 7% of their day getting to their office. Economic Times. Indians spend 7% of their day getting to their office - The Economic Times

The Economic Times. (2024, March 27). Mumbai Coastal Road leads to 5–15% property price rise in western suburbs. Mumbai Coastal Road leads to 5-15% property price rise in western suburbs, ET Infra

Godrej Properties Limited. (2025, June 16). Floor Space Index (FSI): Meaning, calculation and importance. Godrej Properties. https://www.godrejproperties.com/blog/floor-space-index-fsi-meaning-calculation-and-importance

Gupta, S. (2024, March). The Ruin of Mumbai. Asterisk Magazine. The Ruin of Mumbai

Hoe, N., K. Public housing policy in Singapore. National University of Singapore. Public housing policy in Singapore

Hoe, N., K. Public housing policy in Singapore. National University of Singapore. Public housing policy in Singapore

India Today. (2025, June 18). Middle class under pressure: Stagnant wages, high living costs deepen financial stress. Middle class has eroded: Startup founder flags growing financial stress in India

Jang, Y. Seoul Housing Policy. Seoul Solutions. 2. Seoul Housing Policy

Karandikar, M., & Suresh, A. (2024, March 6). Mumbai’s traffic congestion woes: Is proof‑of‑parking the solution? The Takshashila Institution. https://takshashila.org.in/commentary/mumbais-traffic-congestion-woes

Lorenz, M. (2023, May 25). How Vienna found a unique model for low rent. Datawrapper. How Vienna found a unique model for low rent | Datawrapper Blog

Majumdar, D., Tandon, R. (2025, January 30). Living in the city: How much should you earn to have a decent life in Mumbai?. Economic Times. Living in the city: How much should you earn to have a decent life in Mumbai? - The Economic Times

Mehta, M. (2025, June 22). Metro, rail and bus hubs in MMRDA’s plan for Dharavi. The Times of India. Metro, rail and bus hubs in MMRDA’s plan for Dharavi | Mumbai News - Times of India

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. (2023, January 6). Press Note on First Advance Estimates of National Income, 2022‑23. Government of India. https://mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/press_release/PressNote_FAE-2022-23.pdf

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. (2025). Urban transport report: Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Government of India. Economic Survey of Maharashtra 2024-25

Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. (2021). Model Tenancy Act (English) (02.06.2021). Government of India. https://mohua.gov.in/upload/whatsnew/60b7acb90a086Model-Tenancy-Act-English-02.06.2021.pdf

Mujawar, S. N. (2023). The affordability crisis in Mumbai’s housing market: Customer perceptions of rental burden and the search for sustainable living solutions. Maratha Mandir’s Babasaheb Gawde Institute of Management Studies. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391288515_The_Affordability_Crisis_in_Mumbai%27s_Housing_Market_Customer_Perceptions_of_Rental_Burden_and_the_Search_for_Sustainable_Living_Solutions

Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai. (n.d.). Coastal Road Joint Technical Committee Report. https://portal.mcgm.gov.in/irj/go/km/docs/documents/Coastal%20road/Costal%20road%20JTC.pdf

Marpakwar, C. (2020, December 14). Over 500 SRA projects failed to take off in 15 years: Report. Times of India. Over 500 SRA projects failed to take off in 15 years: Report | Mumbai News - Times of India

Nayar, M. (2016, August 5). When Bombay overtook Calcutta: A history of India’s financial capital. Livemint.When Bombay overtook Calcutta: A history of India's financial geography | Mint

Oneindia News. (2025, June 23). Dharavi redevelopment: MMRDA to build integrated multimodal transport hub. Dharavi Redevelopment: MMRDA To Build Integrated Multimodal Transport Hub - Oneindia News

Ray, A. (2024, September 6). Buying a house? These are the most and least affordable cities in India in 2024; full list. Economic Times. Buying a house? These are the most and least affordable cities in India in 2024; full list - The Economic Times

Sanya, S. (2025, March 5). India home prices to climb faster this year; rents even more. Reuters. India home prices to climb faster than inflation this year, rents even more: Reuters poll

Sharma, M. (2025, March 13). Mumbai housing sales up 11% to ₹68,025 cr in Q4; Worli emerges as luxury hotspot. Fortune India. https://www.fortuneindia.com/business-news/mumbai-housing-sales-up-11-to-68025-cr-in-q4-worli-emerges-as-luxury-hotspot/121145

Shrivastava, A. (2025, May 23). Middle class salary crisis: ‘You either become rich or fall behind’ — expert sounds the alarm. Business Today. Middle class salary crisis: 'You Either Become Rich or fall behind' — expert sounds the alarm - BusinessToday

Sirmans, G. S., & Benjamin, J. D. (1991). Determinants of market rent. Journal of Real Estate Research, 6(3), 357–380. (PDF) Determinants of Market Rent

Suhaidab, M., S., Tawila, N., M., Hamzaha, N., Che-Ania, A., I., Basria, H., Yuzainee, M., Y. (2011). Housing Affordability: A Conceptual Overview for House Price Index. Science Direct. Housing Affordability: A Conceptual Overview for House Price Index

http://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/

Thakkar, M. R. (2025, January 2). Real Estate Outlook 2025: 5 most sought‑after areas for buying an apartment in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/real-estate/real-estate-2025-outlook-5-most-sought-after-areas-for-buying-an-apartment-in-the-mumbai-metropolitan-region-101735804916522.html (hindustantimes.com)

Times Now Digital. (2024, May 22). How opening of Mumbai Coastal Road has led to surge in property rates in Bandra-Andheri area. Times Now. How Opening Of Mumbai Coastal Road Has Led To Surge In Property Rates In Bandra-Andheri Area

Vakharia, A. (2024, July 5). Unsold Premium Real Estate Inventory Jumps, But Not A Concern Yet. NDTV Profit. Unsold Premium Real Estate Inventory Jumps, But Not A Concern Yet

Walia, A. (2024, June 17). Over 1 crore flats lying vacant in India; crime to keep assets without utilisation: G Hari Babu. The Indian Express. ‘Over 1 crore flats lying vacant in India; crime to keep assets without utilisation’: G Hari Babu | Business News - The Indian Express

Walia, A. (2025, April 13). ‘30x your income for a 600 sqft in Mumbai’: Reddit post ignites brutal takedown of India’s housing crisis. Business Today. '30x your income for a 600 sqft flat in Mumbai': Reddit post ignites brutal takedown of India's housing crisis

99acres. (n.d.). Property rates and price trends in Mumbai. Retrieved June 21, 2025, from https://www.99acres.com/property-rates-and-price-trends-in-mumbai-prffid\

The views published in this journal are those of the individual author/s and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the team behind Beyond Margins, or the Department of Economics of Sophia College for Women (Autonomous), or Sophia College for Women (Autonomous) in general. The list of sources may not be exhaustive. If you’d like to have the complete list, email us at beyondmarginssophia@gmail.com